Bringing marshes and swamps back to lifein Québec

Major matters | 1

Scientists from the Jardin botanique are building up experience so that they can better restore and protect these endangered ecosystems.

By Annie Labrecque

In Québec, the restoration of peat bogs is well under control. But when it comes to bringing marshes and swamps back to life, knowledge is still limited. And that’s exactly the challenge being taken up by the team of Stéphanie Pellerin and Marie-Hélène Brice, botanists and researchers at the Jardin botanique and the Institut de recherche en biologie végétale, in collaboration with a team from Université Laval. The goal of their project, named Projet RARE: find the best “recipe” for restoring these fragile ecosystems, and propose solutions tailored to each site.

Replanting some trees and a few plants isn’t enough to restore a marsh or a swamp. Every site has unique characteristics: nature of the soil, type of water present (surface or groundwater), flooding duration, plant species in place, and so on. “Unlike peat bogs, where we have a well-established method, there’s no universal approach for restoring a marsh or a swamp,” explains Stéphanie Pellerin. “We have to adapt to each site on the basis of the species found in natural marshes and swamps located nearby.”

On the ground, the first step consists in establishing plant cover using a restricted number of plants (like certain sedge and rush varieties) to limit the invasion of exotic species and re-create the conditions typical of a wetland. “We start by planting local species, and then, over time, we progressively enrich plant diversity,” she explains. The team’s expertise is called on by municipalities and different environmental protection organizations for restoration projects.

In the Farnham area, the team is testing the creation of a microtopography – variations in relief on the ground surface – to observer how that influences tree growth. “We compare the growth of trees planted on mounds with the growth of those installed on flat ground. The idea,” Stéphanie Pellerin sums up, “is to see if these reliefs encourage their development.”

A race against the clock

Wetlands cover about 11 percent of Québec’s territory,1 but are disappearing at an alarming rate. Since colonization, half of them have been destroyed. And it’s not finished: a 2013 study showed that in the St. Lawrence lowlands, one-fifth of remaining wetlands had disappeared since the start of the 2000s. To counteract those losses, the government since 2017 has imposed compensation or restoration measures for destroyed wetlands.

Marshes and swamps play a crucial role in the preservation of biodiversity, in water regulation and in carbon capture. Thanks to the efforts of scientists from the Jardin botanique, Québec is moving little by little towards better protection of those ecosystems.

1 Conservation des milieux humides et hydriques, Ministère de l'Environnement, de la Lutte contre les changements climatiques, de la Faune et des Parcs

What’s the difference between a marsh and a swamp?

Marshes and swamps are two types of wetland where plant life and soils are shaped by water.

Marshes are dominated by herbaceous plants like grasses, flowers and low-growing plants, so they look like a flooded meadow. Swamps, meanwhile, are characterized by the presence of trees and evoke a partly submerged forest.

Marsh

Swamp

The grasshopperthat exists only in the Magdalen Islands

Major matters | 2

For a better understanding of the insect, and to safeguard its protection, a team from the Insectarium is planning to rear specimens.

By Annie Labrecque

The grasshopper Melanoplus madeleineae, which can be found exclusively in the Magdalen Islands, was described for the first time in 1978.1 Unlike certain other species that are able to travel hundreds of kilometers, this one is incapable of flight and is therefore confined to the islands. Come summer, scientists will be making their way there to capture some females with the hope of breeding them and learning more about the species. It’s likely to be a tough job: the insect is hard to spot, since it produces no sound and embraces a nighttime lifestyle.

“Pretty much all its biology is a mystery: its life cycle, its diet, its manner of reproduction, the number of eggs laid,” itemizes Julia Mlynarek, entomologist at the Insectarium. “We don’t even know the size of the population. If some major event were to strike the Magdalen Islands,” she worries, “the species could disappear.” In 2016, a report from the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada already called attention to the grasshopper’s vulnerability.

The nonprofit organization Attention FragÎles, which protects biodiversity on Magdalen Islands territory, has been monitoring the grasshopper population. In 2024, several dozen individuals were observed, compared to just eight in 2023.2 “If it takes the eggs two years to hatch, that could explain the population variation from one year to the next,” Julia Mlynarek believes. Data collected this summer will have an influence on the conservation strategies to be deployed. “To protect the species, its natural habitat has to be preserved,” the researcher insists. That habitat is threatened primarily by climatic and human disturbances.

1 Magdalen Islands Grasshopper (Melanoplus madeleineae): COSEWIC assessment and status report 2016, Government of Canada

2 Rapport d’inventaire; Criquet des Îles-de-la-Madeleine (Melanoplus madeleineae), sur l’archipel des Îles de la Madeleine (Inventory Report: Magdalen Islands Grasshopper [Melanoplus madeleineae] on the Magdalen Islands Archipelago), 2024. Presented to the Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment and Climate Change Canada, Government of Canada. Attention FragÎles, regional environmental council, Magdalen Islands, Québec. 11 pp. Under review.

The challengeof rearing grasshoppers

Breeding grasshoppers in captivity is no easy job! Thierry Boislard, assistant entomologist at the Insectarium, oversees insect breeding and knows how difficult it can be to re-create perfectly the conditions needed to get grasshopper eggs to hatch. In general, those eggs go through a period of diapause, in other words a dormant state that allows them to survive harsh environmental conditions before hatching in the spring.

But in the laboratory, triggering the emergence is a complex matter. “Is it the temperature, the humidity level or the photoperiod that influences hatching?” wonders Thierry Boislard. Finding the right combination of factors is a puzzle. If this summer’s capture comes off as planned and the specimens can be studied under the care of the Insectarium team, the entomologists will have a front-row seat to learning more about its life cycle, its development and its host plants.

And who knows? Maybe we’ll get to admire these grasshoppers one day soon in the Insectarium’s vivariums!

Tracking down environmentalDNA

Major matters | 3

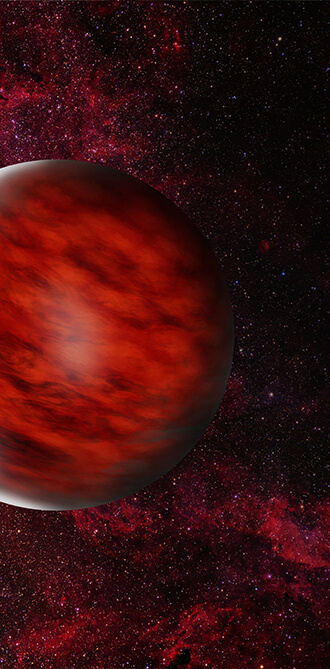

A single sample of water collected in the St. Lawrence River Estuary contains a wealth of secrets about the species evolving in the beluga’s habitat.

By Annie Labrecque

Very soon, people living near the St. Lawrence River Estuary, as well as tourists passing through, will be invited to get involved in a unique community-science project: code Béluga. Their mission? Helping detect the presence of species in the beluga’s ecosystem…by taking a sample of water!

The sampling will be done by following a protocol established by Génome Québec and with the guidance of the Biodôme’s education team. It will be carried out at three points in the year, during spring and summer, at four different locations in the estuary.

But how can a single water sample reveal the presence of species? Every organism releases genetic material in its environment through its feces, its urine, its blood or through skin fragments. This is environmental DNA (eDNA).

“It’s a question of making the invisible visible!”

Francis C. Cardinal, educator and scientific designer at the Biodôme.

Less intrusive than capturing or direct observation, this method will nonetheless shed light on the state of biodiversity and the changing ecosystem of the St. Lawrence Estuary.

The initiative will allow us to mobilize the public around the importance of preserving aquatic ecosystems. The results will afterwards be made available both for research purposes and to the public as a means of supporting efforts aimed at conserving key species in the St. Lawrence.

Discover code Béluga at the Biodôme

The general public visiting the Biodôme will also be able to plunge into this scientific adventure thanks to a series of educational activities relating to the St. Lawrence Estuary, the beluga and environmental DNA.

With code Béluga, community science will unquestionably open a new window on the marine biodiversity of the St. Lawrence!

Discover other conservation projects at Espace pour la vie